The Immigrants of Wellfleet: A History

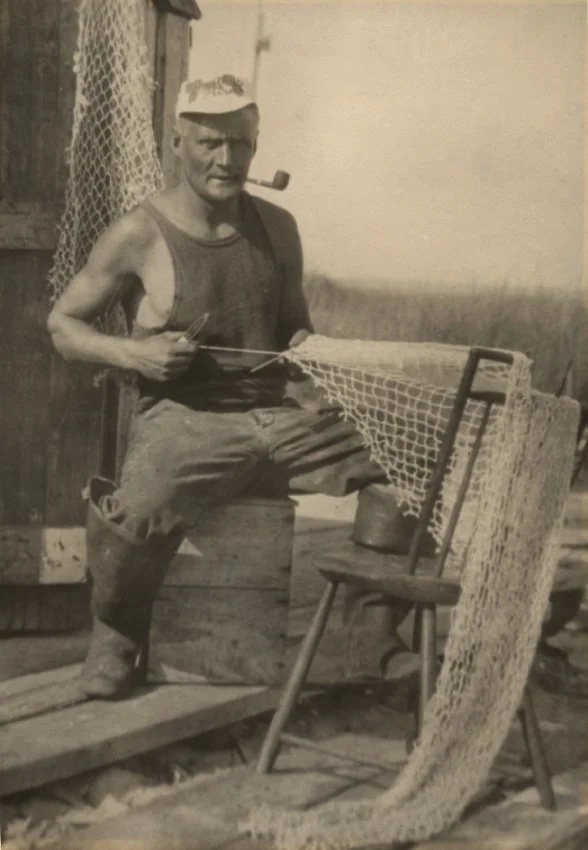

Finnish Wellfleetian circa 1900 (Photo courtesy Wellfleet Historical Society Museum)

By David Wright

Immigrant. Seems like every fourth word we hear today. For some, it means “the other”, someone different, who comes from somewhere else and talks funny. For a seemingly growing few, it refers to those here to take something from us: our land, our jobs, even our dogs and our cats.

Even Native Americans, here far longer than any other ethnic group, had to come on two feet from elsewhere. Somewhere between xenophobia and anthropology lies the truth. But, really, aren’t all humans ultimately from somewhere else each of us just passing through, making our mark?

Recently dated artifacts in the Wellfleet Historical Society Museum show evidence of human activity on Cape Cod dating back 10,000 years. Native Indian culture covered the North and South American continents with strikingly similar concepts of time, space, and governance. The first peoples knew how to work with the land and the sea to sustain themselves, skills they passed on to the Europeans, Cape Cod’s earliest true “immigrants,” who around 1640 began settling on Cape Cod.

Tragically, along with the metal objects they brought for trade – pots, pans, guns, and knives - they brought diseases for which the Native people they met here had no immunity.

It was the English who established the first permanent settlement of Europeans on the Outer Cape. The Pilgrims had known of shellfishing, whaling and agriculture in the Old World; with Indian tutelage, they adapted old methods to their new home, sometimes ensuring their survival. Motivated by the need to earn money, sometimes to pay off debts for their long voyages, they also imposed their Biblically-inspired ideas of man’s rightful dominance over nature. Whereas Native trade was limited and local, by 1665 English settlers were selling Wellfleet oysters in Boston and Salem at such a pace that by 1770 they were mostly gone. To replenish the depleted beds, seed oyster from the Chesapeake Bay was imported to grow here, a practice that continued until WWI. That wave of “immigrants" - oysters - also adapted well.

Other newcomers have also had an impact on the shellfish industry. In 1870, Irish immigrants, many driven from their homeland by the potato famine, completed the railroad, which took Wellfleet oysters to every corner of the country. Those same train tracks brought to town the Italian workers who built the Herring River dike, some of whom elected to stay. Arriving in Wellfleet from Nova Scotia were French Canadians who brought with them their fishing and barrel-making skills, along with the town’s first Catholic Church. Finnish people, fleeing Russian aggression, brought their strong backs to the flats. Around 1900, some of the first women to hold professional shellfish licenses in Wellfleet were of Finnish descent. In the mid-1800s, whaling ships from Wellfleet, Truro, and Provincetown returned with barrels of oil, but also carrying many Cape Verdean whalers who, after whaling’s decline, dominated Provincetown’s fishing industry, and later the burgeoning cranberry industry of Harwich and beyond.

Just as immigrants anchored the Cape’s early fishing industries, they are today providing irreplaceable support to its backbone tourism industry. As they did in the late 1800s, hard-working Jamaicans, brought to Wellfleet in local trading schooners, still play a key role in Wellfleet’s tourism industry, and a growing role in the shellfishing industry. In Provincetown and elsewhere on the Outer Cape, Eastern Europeans keep visitors well-fed and comfortable. It is impossible to imagine any seafood restaurant, kitchen, or motel running without immigrant labor. Many local houses are now painted by Brazilians. As they did one, two, three, and four centuries ago, many of the people who come to Cape Cod to work are choosing to make Cape Cod their home. From Native Americans to today’s Wellfleet oyster, we all came here from somewhere else. And together we make the most savory bouillabaisse...or is that cioppino…or cataplana?

David Wright is the curator of the Wellfleet Historical Society Museum and the author of The Famous Beds of Wellfleet: A Shellfishing History.